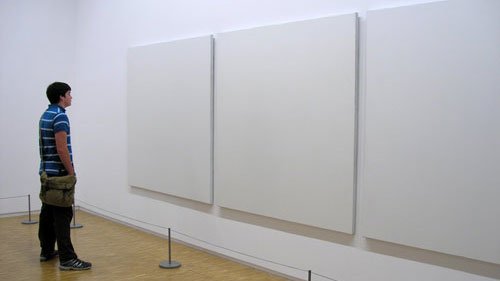

I hate most art museums. I’ll come out and say it. I have been on far too many class trips, city breaks and dates that end with my feigning interest at minimally-labeled canvasses and trying to find some sort of profound meaning in blotches of paint on a canvas—or worse, an apparently-arranged collection of stuff on a pedestal. Sure, I can find some art beautiful, or compelling. This was incredible to see in person, for example. But when art– and nothing else– is all around, I can only maintain interest for so long before creeping boredom overtakes me and I end up revealing my inner plebian.

Don’t get me wrong—I love a good museum. But galleries—like some symphonies and operas—leave me bored and confused. Until recently, I felt this was some deficiency in my character or upbringing. But according to some new research done at the Smithsonian, not only is this commonplace, but more a problem with the museum than with you. And—critically—we can fix it.

A team of sociologists at the Office of Policy and Analysis at the Smithsonian, led by Andrew Pekarik, have published a new theory of museum design and visitation in the January edition of the journal Curator. They call their theory by an acronym: IPOP

According to Pekarik and his team, museum experiences can roughly be split into four categories: those that focus on ideas, on people, on objects, or on physical experiences (hence, IPOP). Different types of museums often break down along these lines—science museums tend to focus on ideas (though the best one incorporate physical experiences, typically), history museums tend to focus on people (though with a secondary focus on objects), galleries are often very object-oriented, and children’s museums are often very physical places.

But interestingly, Pekarik and his team found that this extends not just to museums, but to visitors’ preferences. They write:

These typologies occur in visitors’ own descriptions of themselves, and reflect their own words about what excites them within museums. The evidence suggests that exhibitions that strongly appeal to all four visitor typologies—that leave out no one, in effect—will be highly successful with visitors…

When focusing on visitors, these categories reflect different attractions:

Ideas—an attraction to concepts, abstractions, linear thought, facts and reasons;

People—an attraction to human connection, affective experience, stories, and social interactions;

Objects—an attraction to things, aesthetics, craftsmanship, ownership, and visual language;

and Physical—an attraction to somatic sensations, including movement, touch, sound, taste, light, and smell.

Obviously everyone is drawn to all four of these experience domains in varying degrees. Yet in most of us, one of the four preferences appears to be dominant.

Each of us have preferences; some are excited by ideas but are not particularly fond of physical experiences. Some appreciate objects but could not care less about people. Some have more than one preference, but no-one appreciates all of them equally. And Pekarik and his team are in the process of developing and refining a Meyers-Briggs-esque test to determine what your personal preference is.

Interestingly, this also goes some way to explaining why museums are designed in the way they are. As museums began in the late nineteenth century, they evolved from the curiosity cabinets and private galleries owned by wealthy gentlemen. Both were very object-orientated experiences, and the interpretation (consisting usually only of small labels, or nothing at all) reflected that. Unfortunately, some museums have not transcended these origins; the Sedgwick Museum in Cambridge, England, for better or worse largely retains its nineteenth-century interpretations, with little more than row after row of objects in cases and tiny labels.

But as the twentieth century went on and as new museum-types were developed and innovations made, the range of experiences diversified. But the type of experiences central to each museum was dictated by the museum designers, curators, and directors. These museum professionals each have their own experience-preference, which shapes their work. Part of this is certainly a matter of personal taste and expression, but consonant with last week’s article, part of this certainly is because they may not realize other people are not like them.

This theory has a number of implications, not just in understanding how visitors (like you and me) experience museums, or how designers have built them, but in how they ought to be designed in the future. If their theory is correct, museums of all kinds would be best served by designing exhibits that incorporate as many of these experience-types as possible.

And what does this mean for you as a visitor? Well, it means that the next time your eyes glaze over in a museum or gallery, you can ask yourself: “What’s missing?” In the art gallery, do you want to know more about the artist or subject—or do you want an idea to tie it together? In the history museum, are you frustrated by the fact that you can’t touch the objects? Are there not enough extraordinary things to look at?

You are not alone. And hopefully this framework gives us the tools for understanding not only ourselves—why we react to exhibits in the way we do—but a way of better understanding and critiquing the content of the museums we visit.

For me, I’m an “Ideas” person, with a secondary interest in “People”—which explains my boredom at the Louvre. What are you? And what museums do you love, or hate? Leave your ideas in the comments section below!