A few weeks ago I had the distinct honor—and terror—to load five tightly-packed banker’s boxes onto the back of a FedEx truck, and wave goodbye to them as it drove away. It was a deeply emotional moment, as a culmination of arguably five, but also arguably twenty, fifty, or even two-hundred-and-five years of effort. That is because I was loading the centuries-old historical documents and photos, painstakingly saved by generations of my ancestors, which I have taken to calling the “Martindale/Morley/Nutting Archive,” to be donated to the Amistad Research Center in New Orleans. It is a treasure trove of history.

My family’s archive contains about four hundred letters, half a dozen photo albums with dozens of photographs, two hundred and fifty glass plate negatives, several bunches of legal documents, six daguerreotype photographs in small black and golden cases, a handful of scraps of dresses, about twenty school essays, a large stack of calling cards, reams of research, and a single pressed flower. The earliest letter is from 1817. Most of the collection dates from 1850–1900.

In sending it to Amistad, I hoped—with my heart firmly in my throat—that I was giving it to an institution where it will be preserved and cared for, made accessible for researchers and the public, and loved in the way that I have come to over my years as its steward. I am so grateful that the folks at Amistad have given me every reason to think that this was the right choice, and that this piece of history–that is so much bigger than my family–will be preserved.

And though I have been the one to decide where it would finally go, I am acutely aware of the fact that I was the caretaker—by pure luck, it feels—of the result of centuries of care, work, and love of a line of incredible women. I was the archive’s steward for, maybe, five years (though I hope to continue to be, in a different way). But through its long life, it has been collected, organized, preserved, researched, and passed down through the generations by five other people. I’d like to tell you a little more about them, to honor their memory and their contribution.

It began with Lucy Martindale and the Grand Contraband Camp

The collection was started by Lucy Mary Martindale (1837–1898), my third great grandmother on my mom’s side. Lucy was a prolific writer. Her script is tiny, tight, and neat—entirely appropriate for a time when paper was in short supply. So short, in fact, that sometimes she would fill every inch of the page with what she wanted to say, margins and legibility be damned.

1861 saw the beginning of the US Civil War. Lucy’s beloved, a man named Thomas Milton Morley, enlisted as an officer with the Ohio 2nd Cavalry Regiment. Lucy and Thomas began writing each other letters, and Lucy began keeping a journal. But she was listless at home. So, in 1862 she decided to volunteer with the American Missionary Association (known as the AMA), an abolitionist organization founded by a group of Congregationalist Christians in the North after they helped win the famous United States v. The Amistad Supreme Court case.

In 1863, the AMA sent Lucy to Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. The fort never fell to the Confederacy (despite being within spitting distance of its capital, Richmond). Lucy had been sent there to teach children who had escaped slavery at the “Grand Contraband Camp,” a massive refugee camp for those who had liberated themselves from enslavement. Lucy was one of the first of what W.E.B DuBois would later call the “crusade of the New England school-ma’am”, in which hundreds of Black and white women and men from the North went southwards to teach the hundreds of thousands of newly-freed people.

Lucy kept journals of her time teaching in Virginia, in her small, tight script. And she kept every letter Thomas ever sent her—and convinced him to keep most of the ones that he received too. And so, we have a mostly-unbroken chain of two-way communication between them. That includes the letters when Thomas proposed, and the letter back when Lucy accepted.

That part is very sweet, in a very buttoned-up 19th century sort of way.

Thomas transferred from the cavalry to the artillery, was promoted several times and was made quartermaster for his unit. All the while, he clearly shared Lucy’s penchant for keeping papers. We have letters from his commanding officers, and that he received from at least five others in his family who went to war with him or in other units. When he was discharged due to getting a camp disease, we have the meticulous records of all his paperwork, from a man who had become a professional organizer of things. Lucy also kept many of the other letters she received during the war from friends and family. In particular, we have the letters that Lucy’s 16 year old brother Tim wrote to his mother in the weeks before he died outside of Atlanta.

Lucy kept collecting after the war: letters from their pastor, from family and friends at home and abroad. She kept the letters her sister Hattie sent when committed to Newburgh Asylum from 1874–5, which has been a major source of my reporting debunking the myth of the “Veiled Lady of Kirtland,” leading to the Cleveland Plain Dealer’s 113-year-old correction.

Thomas’ interest in keeping all his correspondence seems to fade, but Lucy’s does not. We have stacks of calling cards from their life in rural Ohio, sheet music which was printed to celebrate the first Thanksgiving declared by Abraham Lincoln in 1863, and albums and albums of photographs of their children. We have many letters to and from the children, their report cards and essays from school, and the letters and newspaper clippings when their daughter Mary died suddenly at the age of 18. We have the letters that Thomas wrote to them all when Lucy fell ill, and the obituary that he wrote when she died.

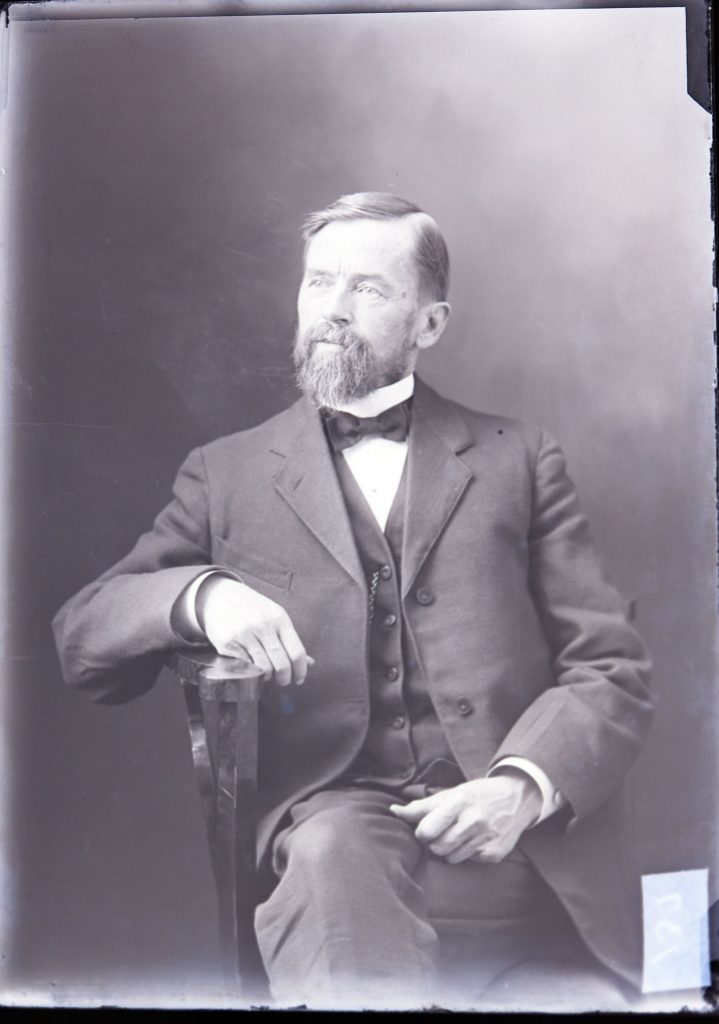

Strangely enough, perhaps, for all that Lucy’s writing stands as a cornerstone of this part of the archive, I have only ever been able to find one surviving photograph of her and of Thomas. Perhaps she was camera shy. Perhaps that was the one thing in her life she did not wish to keep. Or perhaps they were taken out by someone later on, who forgot to replace them.

But we do have one. Here they are: Thomas in the center, seated, with Lucy to his right. Perhaps one day I will find another collection that will reveal some others.

Then, To Lillis Morley Nutting and the Utah Mission Gospel

Thomas and Lucy had six children. Lillis Morley (1865–1961) was the eldest.

In 1890, Lillis married Reverend John D. Nutting, a man who, from what I can tell, was keenly aware of his own importance from the very beginning. There are more portraits of him than of anyone else in the collection. And to be fair, he and Lillis were something of a power couple—at least, in certain rather-specific circles. John D. had graduated from Oberlin, and seems to have been something of a rockstar among the Congregationalist clergy. After they married in 1890, John and Lillis were sent from Cleveland to Salt Lake City by the Congregationalist Church. Their mission was to be a minister and teacher for the small Protestant community living in Mormon-majority Utah.

After a few years, however, John and the other protestant ministers of Salt Lake City decided that they were not doing enough: John was recruited by the Salt Lake City Ministerial Association to go back to Ohio and found the Utah Gospel Mission (UGM), an organization whose sole purpose was to convert the Mormons back to Protestantism, using the Mormons’ own tactics. They sent pairs of young men door-to-door across Utah and the mountain states, meeting with Mormons, passing out literature, and holding revival meetings.

John and Lillis went into this work with gusto. John published prolifically. He is the author of over 40 anti-Mormon tracts with very, very blunt titles: “Why I could never be a Mormon.” “Mormon Twistings of the Bible.” “Eight Reasons why no one should be a Mormon.” My personal favorite title is simply: “Why?”

Lillis was treasurer of the organization—we have accounting books of the UGM in her own handwriting—larger and loopier than Lucy’s, and angled forward as if writing in constant italics. And whenever they were apart, they wrote letters to one another, and to their children. Their letters are very sweet—John invariably opens his letters with one of his innumerable pet names for Lillis, things like “My darling Lillis dear.”

It’s one of the odd juxtapositions of the collection—these sweet, affectionate, deeply personal letters, right next to stacks of firebrand anti-Mormon literature.

It’s very difficult to parse the legacy of all of this. John’s tracts seem always to take aim at the Mormon Church—which I think is a more-than-fair target for criticism—rather than at Mormon people. But inter-religious conflict such as this is worth studying in its full nuance and complexity, and so I hope the materials in the collection help us better understand the past and the perspectives of the people who lived in it.

The collector in this generation seems to have been Lillis. She was clearly interested in the legacy of the Utah Gospel Mission, even though its success in its mission of dismantling the Church of Latter-Day Saints was, shall we say, “limited.” Still, after he died, Lillis arranged for many of John D.’s official papers about the Utah Gospel Mission to be held at Wheaton College (his alma mater), and Bowling Green State University in Ohio. What is in my collection is boxes and boxes of personal correspondence between John D. and Lillis, between Lillis and her intrepid younger sisters, and between all of them and their children.

And also, a centerpiece of those collections are 261 glass plate negatives of photographs taken by UGM missionaries—which gives a rare insight into early Mormon life. Other negatives are already held at Wheaton and Bowling Green State, but I am excited that my family’s archive is now adding another 200 to this collective trove that reveals in detail early Salt Lake City, the Mormon west, and the home and family Lillis and John D. built. It is clearly Lillis who shepherded the collection to a new generation.

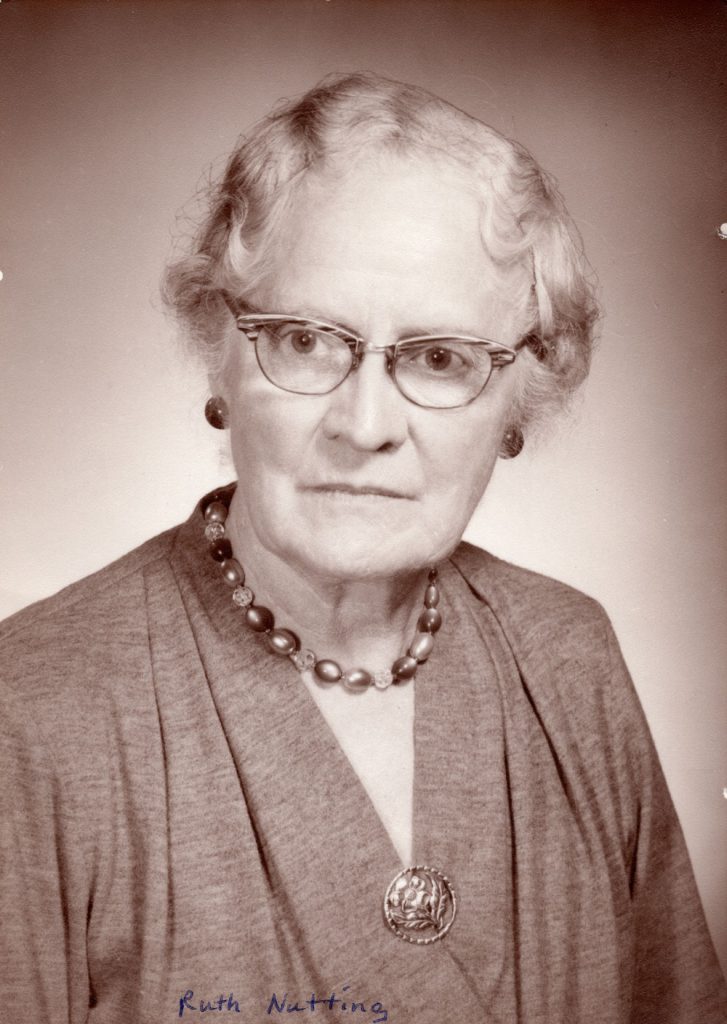

To Lillis Ruth Nutting, the first archivist

Lillis Ruth Nutting (1892–1992) was my great grandaunt—she went by Ruth. She was Lillis Morley and John D. Nutting’s second child. I actually met her when I was young—though she was already 89 years old when I was born! She lived most of her very long life in Cleveland, in an old Victorian house that I suspect might have belonged to Lillis and John D. (though I still have to confirm that). I did my very first oral history project in second grade—I interviewed her and wrote (and illustrated!) a “book,” from it, that I presented to her on her 97th birthday. I found my book in the archive when I inherited it. So, I give it to you, in its totality:

I would like you to meet Ruth Nutting. She really is my great aunt that is 96. I think she is lucky to live 96 years. She has a cat name grey baby that’s because she is grey.

When she was in the Red Cross, she got an award for being there 36 years. When she was a kid she hated to wash dishes. She loved cats and to climb trees.

One of her famous sayings is “SO What?” Her friends say she says it too much.

She thinks “a child should remember what they have learned so some day they will need it.” All of her parents are dead! Do you know anyone that age? Hope she lives to 100!

After my “About the Author” section at the very end, I added more details about her (probably at the insistence of my mother, who likely found the main text a bit lacking in important details). Ruth enjoyed tennis, was a retired teacher, and was born in St. Louis in 1892. She went to Oberlin College, and wanted to live closer to her relatives.

Those relatives, which I did not know at the time, were also famous, in certain circles—Ruth’s aunts (Lillis’ intrepid younger sisters I mentioned above) were Bertha B. Morley and Lucy Morley Marden, retired to California after long lives as relief workers. They were teachers in Ottoman Turkey, and rescued hundreds of children from the Armenian Genocide. Bertha’s journals have become an important first-hand account of the Genocide.

I wish I had more than a second-grader’s perspective on Ruth. Through my fuzzy child’s memory, I mostly remember that her house seemed full of stuff—old newspapers, papers on every surface, and one particular tiny set of brass bells I was very fond of.

What I did not—could not know—is that among those papers in her house, she was acting as the first archivist for this collection. While Lucy and Lillis had mostly collected letters and personal objects to be handed down, Ruth was the first to begin the titanic task of sorting, collating, and preserving everything. She also did research with institutions ranging from the local historical societies to the national archives—I have the forms she filled out, and handwritten family genealogies in her handwriting: large, looping, filling the entire row of the lined notebook paper that she preferred.

And the survival of many of these objects is due to her work. For as long as I was ever aware of them, the glass plate negatives were tightly packed into inscrutable shoeboxes, with each glass plate standing on their long side. In going through them myself, I came to appreciate all that Ruth had done– each negative was given a number with an old-fashioned punch-plastic label maker; each of the slides had a tiny scrap of paper between them, snipped from Cleveland Plain Dealer issues in the early 1970s.

It was only in the last few years that I learned that this is exactly what should be done with glass plate negatives to preserve them. They need to be kept separated from one another lest they stick together and get ruined (though now the separators are foam rather than newsprint). And they should be packed tightly in a box so that they don’t rattle against one another and break. They must be stood on their long edge—the strongest edge—to protect them from breakage and so that gravity does not slowly press them together.

What looked like chaos to the uninitiated was clearly a masterstroke in amateur conservation. And it is telling that only a few of the 200+ slides degraded or broke over the fifty years from when she packaged them in the 70s to when I worked with them in the 2020s.

Finally, one piece of research I particularly appreciate: in a hanging folder, there is a page with a “heraldry” of the sort sold at Renaissance Faires. It’s ostensibly of the Morley family—complete with alleged medieval name origins and family crest. Across the top, written in her wide, looping handwriting, it simply reads: “this is questionable.”

Right on, Aunt Ruth.

To Mary Miles, amateur family historian

Ruth never married and had no children. So, when she died in 1992, the family archive passed to her niece, Mary (Nutting) Miles (1921–2007)—my grandmother. For all the time that I spent with her growing up, I don’t know that I ever really knew my grandmother very well as a person. I knew she worked as a nurse, and that the man I knew as my grandfather was her second husband—her first died very suddenly when my mother was a child.

We would see Mary for Thanksgiving and Easter. I remember her house in Frederick, Maryland: the electric organ in her sitting room, the weeping willow in her backyard, the many books along her walls.

But looking back now, I don’t think I really knew her. When my step-grandfather died in 1998, I thought I might get to know the real Mary. But, it quickly became clear to all of us that she was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, and so the “real” Mary quickly slipped away. In her final years she lost the ability to speak.

But in this archive, I see her work. Her handwriting is mostly print, rather than cursive, and small. I don’t know if she collaborated on the archive with Ruth, but she certainly picked up where Ruth left off.

I have records requests she made to the National Archives, typewritten index cards tracing family relationships, and the first computer printouts of research, family trees, and transcribed documents.

And her research seemed to coincide with her interests. My step-grandfather was in the Air Force. Perhaps that is why in her archival research Mary seemed most interested in military records pertaining to Thomas Milton Morley’s Civil War service, or that of his grandfather in the Revolutionary War.

She also was clearly interested in family genealogical history. From the old-school computerized printouts that she created, she commissioned an artist to create beautifully-rendered watercolor poster-sized family trees for my siblings and I when we were young. Her research into the tree, who they were and their relationships with one another was extensive, particularly considering that she was doing this at the very beginning of the digital age.

While she may have only been the keeper of this archive officially for about 6 years, it is clear that she added significant work in family history to it when it fell into her care.

To Betty Sturtevant, Melissa Pierczynski and Sydney Merz, academic scholars in the digital age

When Mary’s Alzheimer’s became apparent at the end of the 1990s, she came to live with my family for several years. And entirely unbeknownst to me at the time, that archive must have come with her. Mary died in 2007. I first heard about this archive about five years later. I was home from my grad-school studies in England, visiting for the holidays, and I remember this conversation vividly:

Mom: “Paul, you’re a historian.”

Me: “Um…. Yeah…?”

Mom: “We have a box of old family letters. Do you want to take a look at them?”

Me: “Sure, I guess.”

<smash cut to me staring, agog, surrounded by hundreds of Civil War Era letters>

Little did I know that her “box of family letters” was a vast 200-year-old trove of effort to write, to keep, and to pass to the next generation.

I don’t know if my mom worked with the collection before that conversation, but looking at it, it doesn’t seem so. And I get it—it’s incredibly intimidating, and she was a busy, well-respected academic in her own right! But I do know that after that, her interest grew practically overnight. I remember talking with her about what she had been discovering—about Lucy’s teaching, about Thomas’ service, about the mysterious figure of the “veiled lady of Kirtland.” While I was working on my PhD, she started working on this.

My mom, Elizabeth Guiles Sturtevant (1951–2018) was a Professor. She earned her PhD in Education from Kent State University in 1992, and after a brief stint at Marymount University, she settled in for what would become a 25-year career as Professor of Literacy at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. Simply put, she was a leading expert in teaching people to teach reading. Her specialty was adolescent literacy, particularly (I believe), people who did not learn to read at the usual developmental age.

And so, unsurprisingly, the part of the archive that appealed to her most were Lucy’s letters and journals about her time teaching in Virginia. Mom researched the effort to teach those who escaped slavery, and nineteenth century teaching methods. She gave a presentation about Lucy’s teaching at the Literary Research Association conference in 2014, titled “Lucy Martindale’s Diary: A young Ohio teacher’s reflections on her experiences during the Civil War at the “Freedpeople’s” School in Hampton, Virginia,” along with one of her graduate students, Melissa Pierczynski. I have copies of the handouts, but no script of what she said. If she was anything like me, she may have written it in the hotel the night before—though something tells me she would have prepared a little more for this one than I often do.

But my mom’s handwriting isn’t in the archive. Part of this is because she was the first person to work on it truly in the digital age. She made Google Maps outlining Lucy’s travels, used Google Books to find the mentions of her in other scholarship, she scanned the letters, numbered them, and organized them into archival-grade acetate sleeves, acid-free folders, and archival boxes. And she transcribed them—or rather, she had them transcribed; a few by me, but most by her graduate students, Melissa Pierczynski and Sydney Merz.

The other reason her handwriting is not there is because my mom was suffering from a very rare combination of early-onset Parkinson’s Disease, and a rare neurodegenerative disorder called Multiple System Atrophy. She wanted to do more research into Lucy’s life and teaching. She wanted to present more, to write papers about it, maybe a book. She didn’t get the time. She died March 29th, 2018.

To Me, and to the Amistad Research Center

And so, it came to me.

Inheritances are often a bit of a mess. Inheriting this archive was not an exception. I’m still not convinced I have all of my mother’s notes, and I know I’m missing a large tranche of letters that I hope to recover one day. And I personally know that taking on the mantle of caretaker at precisely the moment of reeling from deep trauma can lead to a lot of mixed feelings.

At first, it felt like a burden that I had no idea how to shoulder. How to make heads or tails of all of this? Could I continue my mother’s work? Could I turn this into articles, or even a book? Sure, I’m an historian, but my specialty is medievalism and public history, not 19th-early 20th century America. And besides, I live in a small DC apartment. I don’t have the space to keep and work with such an enormous trove!

For a few years, I put it in a climate-controlled storage unit, and tried to forget it existed.

But, after some time, I started to look at it again. As I began to reconsider what I wanted to do with my life, and where I wanted to go, I knew that it wasn’t doing anyone any good just sitting in storage.

I started by picking up the thread I helped my mom research when she was alive, about Lucy’s teaching. I did what historians do: I checked the bibliography of that scholarship that mom found. All of the books that discussed her or the teaching at Fort Monroe drew upon primary sources held at one place: the Amistad Research Center. Amistad was founded to house the archives of the American Missionary Association. But was the anti-Mormon material right for Amistad? What about Harriet’s “Veiled Lady” story, or all the other bits and pieces not seemingly related? Would they even be interested in it?

So, I reached out to the archivists at Amistad, and the response was resounding: They. Wanted. Everything. I learned that it is good archival practice not to split up an existing collection, and more, their purview extends to Congregationalism in general—which includes Lillis’s writings, and all the other family materials.

And so, Amistad it was.

From there, it was just a simple matter of cataloging and collating everything, transcribing the rest of the Civil-War era soldiers’ letters, getting sucked down the rabbit hole of solving the mystery of the “Veiled Lady of Kirtland,” repackaging hundreds of photos, letters, and oh-god-please-don’t-break glass negatives, digitizing and photographing what I could, having the whole thing professionally appraised, and filling out lots and lots of paperwork. This is the part where my partner Arielle Gingold (who is also my editor and go-to packing Tetris expert) joked, “ok, maybe not that simple.”

And then packing it tightly into five banker’s boxes and giving it to a friendly and kind Fedex employee who, seeing my anxiety, promised to send photos and updates every step of the way. A promise that she made good on.

So, that’s the story. The provenance. The history of this history. The people who lived, created, preserved, and shared it. I am humbled, honored, and in awe of the fact that I have been able to bring a kind of conclusion—or hopefully a new life—to work begun over 160 years ago. I am eternally grateful to all of these women–in my family and not–for keeping these precious things safe over the centuries.

I had a nice talk with Syd the other week. She related a conversation she had with my mother years ago when they were working on Lucy’s letters together. Mom confessed to Syd that she deeply feared that the work on and with this archive would end with her.

I hope I’ve done what she wanted.

Because even if I were to die tomorrow (though I have no plans to), I know that now, thanks to the folks at Amistad, the work will not end. I hope to continue my part of the work when and how I can. But I’m relieved that it’s no longer up to just me.

So, Lucy, Lillis, Ruth, Mary, Betty, Melissa, Syd, Arielle. Thank you. I hope I’ve done you proud.